Khirbet el-Mastarah, 2017

The site of JVEP’s first excavation was at Khirbet el-Mastarah, which was an intriguing site from the beginning. Its name, “Mastarah,” is derived from a root that means “to hide,” and the site is literally hidden. It is located in the desert, about four miles north of Jericho, off the main roads and away from reliable water sources. It is positioned in the fork of a wadi and surrounded by hills on three sides, completely masked from its surroundings.

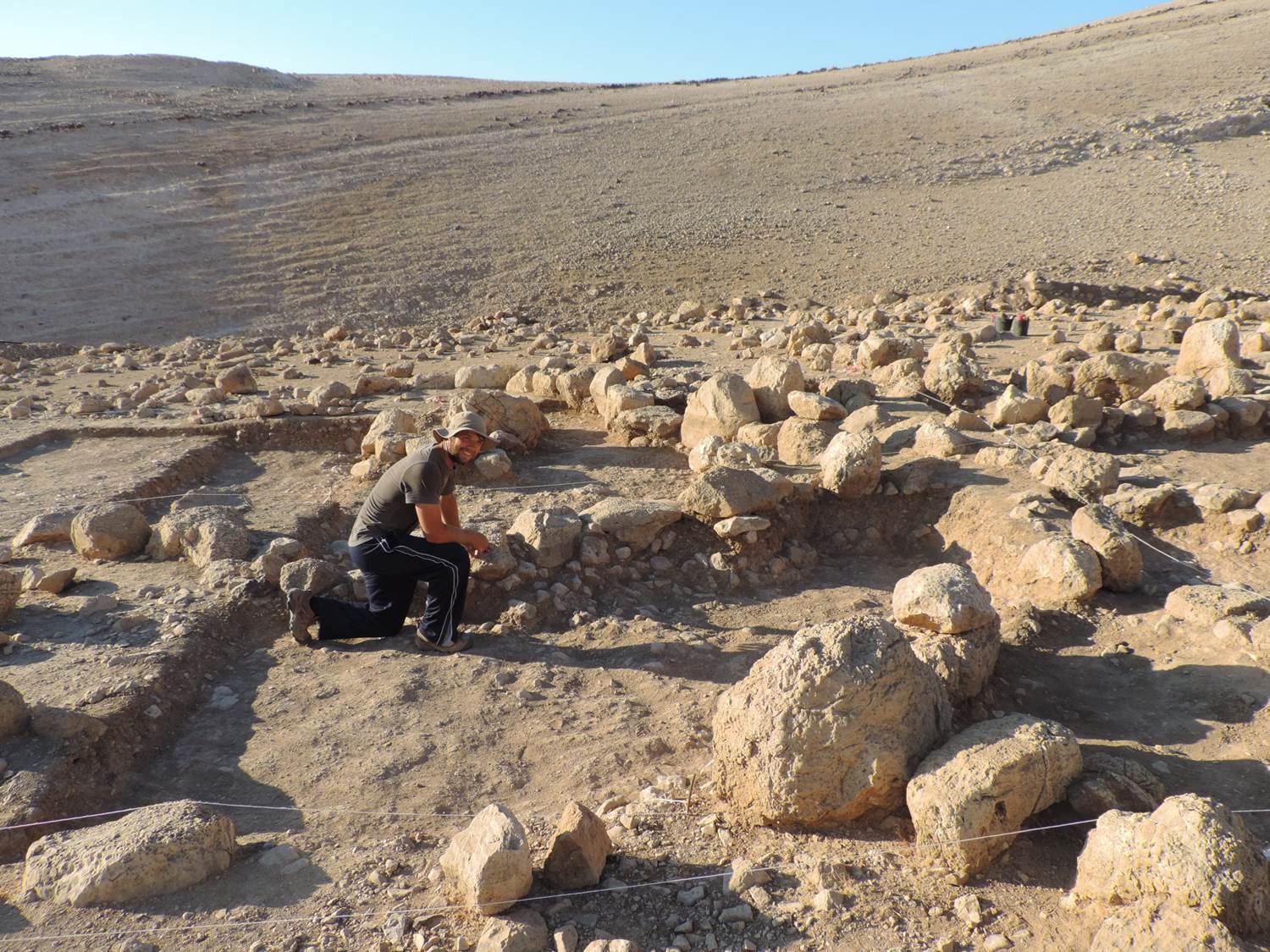

The 2.5 acre site consists of a number of enclosures and small structures. With a team of about fifteen students and volunteers from America, Canada, Israel, China and Australia, we dug six test trenches in the main site, and three in two subsidiary sites. Altogether, we excavated fourteen complete 5 x 5 meter squares, along with six partial squares, adding up to a total excavated area of about 400 m2.

El-Mastarah contains three types of architectural units, including large rounded enclosures (over 3 m in diameter), small rounded or oval enclosures (usually between 2-3 m in diameter), and rectilinear units. The walls, which are built of rubble stones typically about a half meter in size, were all only a single course in height, and usually only one row thick. Our excavation areas included rounded enclosures, oval units, lengths of walls, open areas, and several areas where there were a lot of large stones but where no clear architecture could be defined. One oval unit that we excavated had an entrance with a large flat stone that served as a threshold. One of our volunteers, who had received a BAR Dig Scholarship, found two large basalt grinding stones inside one unit. These appear to have been in situ on a floor. She also found a few bones, all from sheep or goat. However, most of the excavated areas were almost entirely devoid of finds, and we were therefore unable to establish a firm date for the architecture.

Our pottery repertoire contained some sherds from two kraters that date either to the Late Bronze II (1400-1200 BCE) or the Iron Age I (1200-1000 BCE). There were also 26 Iron Age sherds, and 8 of these came from cooking pots. Three of these date to the Early Iron Age I (1200 BCE) or the beginning of the Iron Age II (1000 BCE). This is interesting, since a large proportion of cooking pots was also noted in the Iron Age assemblage at several of the “sandal” sites discovered in the Jordan Valley.

Our aim at el-Mastarah had been to determine the date and function of the structures that were already visible above ground before we excavated. However, the absence of any finds prevented us from establishing the date of their construction and use. They seem to have been built in the same period, since there was no evidence that the structures cut into or overlay each other. Based on the sherds found by the survey and during the excavation, it appeared that the site was founded in the Middle Bronze II (2000-1550 BCE), functioned mostly during the Iron Age (1200-586 BCE), and was reused during later periods, especially the Roman period (37 BCE-324 CE). But we could not date the structures. Everywhere we dug, when we reached between 0.2-0.8 meters, we reached a sterile layer, with no finds at all. This raised two important questions. First, why were the structures sterile? And, second, why was there no development at the site?

In looking for answers to this puzzle, we began studying current Bedouin settlement and various ethnographic studies, and we found that animals are often housed in enclosures while the people live in tents around them. In such cases, the Bedouin sometimes live at some distance from the enclosures. We also examined the survey reports of the other enclosure sites in the Jordan Valley, and found that the material finds in the Iron Age I enclosures and the composite settlements are generally quite meagre, with a scarcity of pottery, which suggests that they may be seasonal settlements. We concluded that the inhabitants of el-Mastarah might not have lived in the enclosures, but instead corralled their cattle there while they lived in tents around the site, possibly at some remove.

Since there were not enough earlier communities in the surveyed areas to provide a source for the new population associated with these sites, we also concluded that the settlers must represent a new population from outside the region. The new settlers were connected with a process of tribalization that was occurring in the region during the transition from the Late Bronze Age (1550-1200 BCE) to the Iron Age I (1200-1000 BCE), possibly connected with the tribes of Israel.

To read our July/August 2018 Biblical Archaeology Review article, click here.